thumbnails/m045_ed80f075_20d-nr_4x20minseciso1600_sigmed_ip-ddp2061.jpg M45 Pleides Cluster (Seven Sisters) (2006) - Dave Samuels |

|---|

| Acquisition Date | : | 08/27/2006, Fremont Peak, California | | Camera | : | Canon 20D unmodified about 54 degrees F | | Camera Settings | : | 4 cr2 raw frame -

4 x 20min 1600ISO RAW, with save to PC and convert upon download. Also included JPG, which I like to do so I can check on things without having to do a lot of processing.

Darks, flats and bias taken just before sunrise.

In-camera noise reduction ON

Mirror lock off | | Telescope/Optics | : | 600mm f/7.5 Orion ED80. | | Mount | : | AP1200 2006 series

guided through Orion ST80 (400mm f/5.0) with DSI IIc, GPUSB shoestring, MaximDL

| | Adapter / Prime / Afocal / Other | : | None

North is up in this image, though it was to the left in the source images due to the way I have to place the camera on the mount, | | Weather/Conditions | : | Clear - seeing was as good. | | Processing Package / Processing Applied | : | Manually focused using IP fwhm focus data. Captured using Images Plus 2.75 for focus/capture/calibrate/align/stack averaged. | | Web Site | : | www.davesamuels.com | | NOTES | : | M45 is located at RA 3h 46.807m, DEC +24deg 11.355' (J2000)

Notice the small galaxy just to the right of Electra (on the right side of the image RA 3h 43.742m, DEC +24deg 3.644'). It is UGC 2838 at 17.29 mag (StarryNight - 17.89 by other accounts). |  m042_55_140mmf070_20d-nr_120SecISO800_10xSigMed_ip-crop-ddp2114-astrotools.jpg

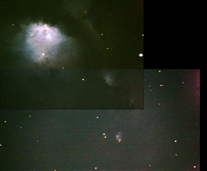

M42 - The Great Orion Nebula M42 - The Great Orion Nebula

Messier 42 is a starforming Nebula M42 (NGC 1976), an emission and reflection nebula, with Open Star Cluster, in the constellation Orion.

Right Ascension 05 : 35.4 (h:m)

Declination -05 : 27 (deg:m)

Distance 1.3 (kly)

Visual Brightness 4.0 (mag)

Apparent Dimension 85x60 (arc min)

Taken with TEC 140mm f/7.0. Canon 20D with in-camera noise reduction at 800iso. 10x2min images registered and stacked in ImagesPlus and tweaked in PS.

Temperature was about 55 degrees and dropping.

Excerpt from seds.org:

Of the hundreds or possibly thousands of images I've taken of this object, this image is by far the best quality and detail of them all to date.

The Orion Nebula was possibly discovered 1610 by Nicholas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc.

Independently found by Johann Baptist Cysatus in 1611.

Trapezium cluster found as multiple star by Galileo Galilei in 1617.

The Orion Nebula Messier 42 (M42, NGC 1976) is the brightest starforming, and the brightest diffuse nebula in the sky, and also one of the brightest deepsky objects at all. Shining with the brightness of a star of 4th magnitude, it is visible to the naked eye under moderately good conditions, and rewarding in telescopes of every size, from the smallest glasses to the greatest Earth-bound observatories as well as outer-space observatories like the Hubble Space Telescope. It is also a big object in the sky, extending to over 1 degree in diameter, thus covering more than four times the area of the Full Moon.

As it is so well visible to the naked eye, one may wonder why its nebulous nature was apparently not documented before the invention of the telescope. Only some Central American, Mayan folk tales may be interpreted in a way suggesting that these native Americans may have known of this nebulous object in the sky (O'Dell 2003, p. 3). However, the brightest stars within the nebula were noted early and cataloged as one bright star of about fifth magnitude: In about 130 AD, Ptolemy included it in his catalog, as did Tycho Brahe in the late 16th century, and Johann Bayer in 1603 - the latter cataloging it as Theta Orion in his Uranometria. In 1610, Galileo detected a number of faint stars when first looking at this region with his telescope, but didn't note the nebula. Some years later, on February 4, 1617, Galileo took a closer look at the main star, Theta1, and found it to be triple, at his magnification of 27 or 28x, again not perceiving the nebula.

The Orion Nebula was probably discovered in late 1610, when Nicholas-Claude Fabri de Peiresc (1580-1637), a French lawyer, turned his telescope to this region of the sky, and reported of a cloudy nebulosity. This sighting, however, was not published, but only reported in Peiresc's personal documents and brought up only by Bigourdan (1916). It was independently found in 1611 by the Jesuit astronomer Johann Baptist Cysatus (1588-1657) of Lucerne who compared it to a comet he had observed in the year 1618 (Cysat 1619). This work also did not get widely known, and opnly turned up by Rudolf Wolf in 1854 (Wolf 1854). The first known drawing of the Orion nebula was created by Giovanni Batista Hodierna, who included three stars; these are probably Theta1 as well as Theta2A and Theta2B. All these discoveries apparently got lost for some time, so that eventually Christian Huygens was longly credited for his independent rediscovery in 1656, e.g. by Edmond Halley who included it in his list of six "nebulae" (Halley 1716), by Jean-Jacques d'Ortous de Mairan in his nebulae descriptions, by Philippe Loys de Chéseaux in his list, by Guillaume Legentil in his review, and by Charles Messier when he added it to his catalog on March 4, 1769.

It is somewhat unusual that the Orion Nebula has found its way into Messier's list, together with the bright star clusters Praesepe M44 and the Pleiades M45; Charles Messier usually only included fainter objects which could be easily taken for comets. But in this one night of March 4, 1769, he determined the positions of these wellknown objects, (to say it with Owen Gingerich) `evidently adding these as "frosting" to bring the list to 45', for its first publication in the Memoires de l'Academie for 1771 (published 1774). One may speculate why he prefered a list of 45 entries over one with 41; a possible reason may be that he wanted to beat Lacaille's 1755 catalog of southern objects, which had 42 entries. Messier measured an extra position for a smaller northeastern portion, reported by Jean-Jacques d'Ortous de Mairan previously in 1731 as a separate nebula, which therefore since has the extra Messier number: M43.

As the drawings of the Orion Nebula known to him did so poorly represent Messier's impression, he created a fine drawing of this Object, in order to "help to recognize it again, provided that it is not subject to change with time" (as Messier states in the introduction to his catalog).

This gorgeous object continued to influence astronomers since. It was the first deepsky observation by William Herschel with a self-constructed reflecting telescope of 6-foot focal length in 1774. In 1789, with some prophetic touch, he described his observations with his 48-inch aperture, 40-foot FL scope as "an unformed fiery mist, the chaotic material of future suns."

The gaseous nature of the Orion Nebula was revealed in 1865 with the help of spectroscopy by William Huggins. On September 30, 1880, M42 was the first nebula to be successfully photographed, by Henry Draper. Consequently, on March 14, 1882, Henry Draper obtained a second, better, deeper, and more detailed photograph of the Orion Nebula, a 137-minutes exposure, which also clearly shows M43.

The Orion Nebula is located at a distance of about 1,600 (or perhaps 1,500) light-years. At this distance, its angular diameter of 66x60 arc minutes corresponds to a linear diameter of about 30 light-years. On its northern end, the nebula is devided by a conspicuous dark lane, well visible in our photograph. This image was obtained David Malin of the Anglo-Australian Observatory. More information on this image is available.

The detached northeastern portion is the nebula M43 first reported by De Mairan, and listed as a separate nebula by Charles Messier. Like the main nebula M42, this is an emission nebula, shining by the light emitted from its atoms, after being excited by the high-energy radiation of massive, very hot young stars within it. In the very neighborhood, to the north, there are also fainter reflection nebulae, partially reflecting the light of the Great Nebula. They were not notable for Charles Messier, but labeled later with the NGC numbers 1973, 1975, and 1977: NGC 1977 had been found by William Herschel (his H V.30), while NGC 1973 and NGC 1975 are discoveries of Heinrich Ludwig d'Arrest. Here we have a collection of more images of M42, M43, and more images of M42, M43 and NGC 1973-5-7.

The Orion Nebula is the brightest and most conspicuous part of a much larger cloud of gas and dust which extends over 10 degrees well over half the constellation Orion. The linear extend of this giant cloud is well several hundreds of light-years. It can be visualized by long exposure photos (see e.g. Burnham) and contains, besides the Orion nebula near its center, the following objects, often famous on their own: Barnard's Loop, the Horsehead Nebula region (also containing NGC 2024 = Orion B), and the reflection nebulae around M78. Already impressive in deep visible light photographs, the Orion Cloud is particularly gorgeous in the infrared light.

M42 itself is apparently a very turbulent cloud of gas and dust, full of interesting details, which Charles Robert O'Dell has compared to the rich topography of the Grand Canyon in his HST photo caption. The major features got names on their own by various observers: The dark nebula forming the lane separating M43 from the main nebula extends well into the latter, forming a feature generally nicknamed the "Fish's Mouth". The bright regions to both sides are called the "wings", while at the end of the Fish's Mouth there's a cluster of newly formed stars, called the "Trapezium cluster". The wing extension to the south on the east (lower left in our image) is called "The Sword", the bright nebulosity below the Trapezium "The Thrust" and the fainter western (right) extension "The Sail". Here we have a small collection of Images of detail in M42, including another nomenclature for the brightest region in the nebula by historic visual observers, as well as a pictorial study of the Trapezium cluster and region by Lowell Observatory images.

The Trapezium Cluster is among the very youngest (open) clusters known, with new stars still forming in this region. As stated above, the cluster was first depicted as triple star on February 4, 1617 by Galileo, who was not aware of the nebula. Galileo's discovery did not get widely known, so that Christian Huygens independently rediscovered the triple star in 1656 together with the Orion Nebula. These first three stars are often labelled "A", "C", and "D". It may be of interest that in both cases, the Trapezium, or Theta1 Orionis, was second to only one other double star: Mizar (Zeta Ursae Majoris). The fourth Trapezium star, "B", was first found by Abbe Jean Picard in 1673 (according to De Mairan), and independently by Huygens in 1684. The fifth cluster star "E" was discovered by Friedrich Georg Wilhelm Struve in 1826 with a 9.5-inch refractor in Dorpat, the sixth, "F", by John Herschel on February 13, 1830, the seventh, "G", by Alvan Clark in 1888 when testing his 36-inch refractor of Lick Observatory, and the eighth, "H" by E.E. Barnard later in 1888 with the same telescope. Barnard later found that "H" is double, with two 16th-magnitude components. Today we know that stars "A" and "B" are both eclipsing variables of Algol type: A (also known as V1016 Ori) was discovered in 1975 to vary between magnitudes 6.73 and 7.53 with a period of 65.4325 days, while B (also cataloged as BM Ori) varies between mag 7.95 and 8.52 in 6.4705 days, and is always the faintest of the four Trapezium stars.

The past decades of research on the Orion Nebula have revealed that the visible nebula, M42, the blister of hot, photo-ionized, luminous gas around hot Trapezium stars, is only a thin layer lying on the surface of a much larger cloud of denser matter, the Orion Molecular Cloud 1 (OMC 1). We happen to see this structure approximately face-on. The idea for this model came originally from Münch (1958) and Wurm (1961) and fully elaborated by several authors around 1973-1974 (Zuckerman (1973), Balick et.al. (1974)), soon supported by evidence, and is still studied in detail, see e.g. O'Dell (2001) for a recent review, and references cited therein. The San Diego Supercomputer Center (SDSC)'s VisLab has created a 3-dimensional visualization of the Orion Nebula based on this model (see side-view model image of M42).

The Orion nebula was, continuously since the early times before its refurbishment, a preferred target for the Hubble Space Telescope. One major discovery was that of protoplanetary disks, the socalled "Proplyds" (planetary systems in formation) in these HST images of M42 (these images were used for an animation simulating the approach to a protostar [caption]). HST images of November 1995 have revealed further insight into the complicated process taking place in this "star factory". Hubble investigations of January 1997 have revealed interesting interactions of the young hot Trapezium cluster stars with the protoplanetary disks: Their violent radiation tends to destruct the discs, so that the lower-mass stars forming here may loose the material needed to form planetary systems.

In 1982, a symposium solely devoted to the Orion Nebula was held to celebrate New York University#s Sesquicentennial, and to honor the one hundredth anniversary of the first photograph of the Orion Nebula taken by Henry Draper on September 30, 1880 (Glassgold et.al. 1982).

An excellent review of the astrophysics of the Orion Nebula is provided in 2003 with the superb monograph by Charles Robert O'Dell (O'Dell 2003), who summarizes the knowledge of that time, including HST research.

It is very easy to find the Orion Nebula, as it surrounds the Theta Orionis multiple star or cluster, seen to the naked eye in the middle of the sword of Orion. Already under fairly good conditions, the nebula itself can be glimpsed with the naked eye as a faint nebulosity around this star.

The Orion Nebula is also one of the easiest and most rewarding target for amateur astrophotographers.

(m042_55_140mmf070_20d-nr_120SecISO800_10xSigMed_ip-crop-ddp2114-astrotools.jpg)  ngc2244-rosette-neb_40deg_140mmf070_20d-nr_3x480SecISO1600_Avg_ip-ddp2473-astrotools-sat-crv_ninja.jpg

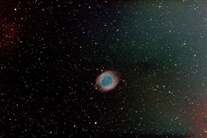

The Rosette Nebula - (NGC 2244) and NGC 2237-9,46, Diffuse Nebula NGC 2237-9,46, Open Cluster NGC 2244 (= H VII.2), type 'c', in Monoceros

Rosette Nebula taken with TEC140mm f/7.0, canon 20d with in-camera noise reduction. 3x8mins at 1600 iso from backyard in bay area. Stacked with Images Plus 2.83, then processed in PhotoShop with astrotools, color saturation, curves, and Noise Ninja.

The Rosette Nebula - (NGC 2244) and NGC 2237-9,46, Diffuse Nebula NGC 2237-9,46, Open Cluster NGC 2244 (= H VII.2), type 'c', in Monoceros

Right Ascension 06 : 32.3 (h:m) 06 : 32.4 (h:m)

Declination +5 : 03 (deg:m) +4 : 52 (deg:m)

Distance 5.5 (kly) 5.5 (kly)

Visual Brightness ? (mag) 4.8 (mag)

Apparent Dimension 80x60 (arc min) 24 (arc min)

Discovered by John Flamsteed about 1690.

Excerpt from seds.org:

The Rosetta Nebula is a vast cloud of dust and gas, extending over an area of more than 1 degree across, or about 5 times the area covered by the full moon. Its parts have been assigned different NGC numbers: 2237, 2238, 2239, and 2246. Within the nebula, open star cluster NGC 2244 is situated, consisted of the young stars which recently formed from the nebula's material, and the brightest of which make the nebula shine by exciting its atoms to emit radiation. Star formation is still in progress in this vast cloud of interstellar matter; a recent finding of a very young star with a Herbig-Haro type jet by astronomers at the NOAO has been announced in Press Release NOAO 04-03 on January 22, 2004.

Although various values for its distance occur in the literature, our adopted distance from the Sky Catalog 2000 implies a true diameter of the nebula of about 130 light years. Burnham quotes a mass estimation of 10,000 (Minkowski 1949) to 11,000 (Menon 1962) solar masses, so it is one of the more massive diffuse nebulae.

Open cluster NGC 2244 was discovered by Flamsteed about 1690. The nebula, however, was not even seen by William Herschel (who found the cluster); its different parts were discovered only by John Herschel (NGC 2239 = GC 1420 = h 392), Marth (NGC 2238 = GC 5361 = Marth 99), and Swift (NGCs 2237 and 2246); note that while now these numbers are used for describing parts of the diffuse nebula, their original NGC description is quite different:

2237 pretty bright, very very large, diffuse (?= [GC] 5361 [= NGC 2238])

2238 small [faint] star in nebulosity

2239 star of mag 8 in large, poor, bright cluster

2246 extremely faint, large, irregularly round, extremely difficult

Nevertheless, the nebula is a splendid object, especially for astrophotography.

(ngc2244-rosette-neb_40deg_140mmf070_20d-nr_3x480SecISO1600_Avg_ip-ddp2473-astrotools-sat-crv.jpg)

b33-horsehead_ed80f075_20d-nr_3x20min_iso800_ip-flat-adpadd-ddp1649_pe-despeks1.jpg

b33-horsehead_ed80f075_20d-nr_3x20min_iso800_ip-flat-adpadd-ddp1649_pe-despeks1.jpg (b33-horsehead_ed80f075_20d-nr_3x20min_iso800_ip-flat-adpadd-ddp1649_pe-despeks1.jpg)

comet-73p_20d_k3_nr_180seciso3200_000002_ps-lvl-snr-dsnr-lpr-curve_pe-despkl.jpg

comet-73p_20d_k3_nr_180seciso3200_000002_ps-lvl-snr-dsnr-lpr-curve_pe-despkl.jpg (comet-73p_20d_k3_nr_180seciso3200_000002_ps-lvl-snr-dsnr-lpr-curve_pe-despkl.jpg)

comet-faye4p__ed80f075_20d-nr_300seciso1600_ip-ddp11416.jpg

comet-faye4p__ed80f075_20d-nr_300seciso1600_ip-ddp11416.jpg (comet-faye4p__ed80f075_20d-nr_300seciso1600_ip-ddp11416.jpg)

comet-machholz_q2_2004__adpadd23_dd_cropped.jpg

comet-machholz(q2 2004)_adpadd23_dd_cropped.jpg (comet-machholz(q2 2004)_adpadd23_dd_cropped.jpg)

comet-swan-m4_20d-nonr_8min_maxim.jpg

comet-swan-m4_20d-nonr_8min_maxim.jpg (comet-swan-m4_20d-nonr_8min_maxim.jpg)

comet-swan-m4_20d-nonr_maxim.jpg

comet-swan-m4_20d-nonr_maxim.jpg (comet-swan-m4_20d-nonr_maxim.jpg)

comet-tempel1_filesavg9.jpg

comet-tempel1_filesavg9.jpg (comet-tempel1_filesavg9.jpg)

comet-tempel10607051230_postimpact.jpg

comet-tempel10607051230_postimpact.jpg (comet-tempel10607051230_postimpact.jpg)

11/17/2007

Comet Holmes/17p

This comet exploded from a 17mag comet to about 3mag overnight. At mag 3, it was visible to the naked eye for several months and grew to a size larger than the sun. The change was discovered around October 22. My first images in the backyard were around Nov 5. In this highly processed image, you can clearly make out several jets streaming from the comet. What looks like the core of the comet is merely more dense gases surrounding the core.

This image is a single 30sec image at 1600 iso using a 28mm-300mm Sigma zoom lens at 300mm f/5.6 on a tripod with no tracking.

(IMG_0686.jpg)

11/17/2007

Comet Holmes/17p

(IMG_0694.jpg) holmes17-comet_735f480_20d50deg_241sec_IMG_0693_ps-crv-hipass-lvl-usm_ninja.jpg

holmes17-comet_735f480_20d50deg_241sec_IMG_0693_ps-crv-hipass-lvl-usm_ninja.jpg

11/17/2007

Comet Holmes/17p

This comet exploded from a 17mag comet to about 3mag overnight. At mag 3, it was visible to the naked eye for several months and grew to a size larger than the sun. The change was discovered around October 22. My first images in the backyard were around Nov 5. In this highly processed image, you can clearly make out several jets streaming from the comet. What looks like the core of the comet is merely more dense gases surrounding the core.

This was a single 241 second image using the 764mm f/4.8 Challenger scope and processed using photoshot hipass filtering.

(holmes17-comet_735f480_20d50deg_241sec_IMG_0693_ps-crv-hipass-lvl-usm_ninja.jpg)

coyote_hildebrandt_dsc00026.jpg

coyote_hildebrandt_dsc00026.jpg (coyote_hildebrandt_dsc00026.jpg)

A coyote we encounted on the way down from Nancy's place. Ground is frosty. We got within about 40 yards when it took off chasing after three female coyotes.

fpoaobservatoryfromfremontpeak_dsc00152.jpg

fpoaobservatoryfromfremontpeak_dsc00152.jpg (fpoaobservatoryfromfremontpeak_dsc00152.jpg)

m001-crab_45deg_ed80f150_20d-nr_3x1200seciso800_ip-adpadd-ddp2960-crop.jpg

m001-crab_45deg_ed80f150_20d-nr_3x1200seciso800_ip-adpadd-ddp2960-crop.jpg (m001-crab_45deg_ed80f150_20d-nr_3x1200seciso800_ip-adpadd-ddp2960-crop.jpg)

M1 - Crab Nebula.

Image taken with Orion ED80 with 2" Orion Barlow and Canon 20D with internal nose reduction on. It is a stack of 3 images at 20mins each at 800 iso. Images Plus 2.83 adaptive add with DDP at 2960 and cropped to accentuate the nebula.

M1 is a supernova remnant, from a supernova in 1054 AD. Chinese history says that it was so bright that it cast a shadow. It was visible for a long time during the day and for months or years (I forget) at night. For the longest time, it was the brightest object in the sky. This is the first supernova within our galaxy that was recorded in history and witness by humans. The gas clouds continue to move away from the center at a rapid velocity. In addition, I believe the first pulsar was discovered in the center of the crab nebula using radio telescopes.

Messier 1

Supernova Remnant M1 (NGC 1952) in Taurus

Crab Nebula

Right Ascension 05 : 34.5 (h:m)

Declination +22 : 01 (deg:m)

Distance 6.3 (kly)

Visual Brightness 8.4 (mag)

Apparent Dimension 6x4 (arc min)

Discovered 1731 by British amateur astronomer John Bevis.

Excerpt from seds.org:

The Crab Nebula, Messier 1 (M1, NGC 1952), is the most famous and conspicuous known supernova remnant, the expanding cloud of gas created in the explosion of a star as supernova which was observed in the year 1054 AD. It shines as a nebula of magnitude 8.4 near the southern "horn" of Taurus, the Bull.

The supernova was noted on July 4, 1054 A.D. by Chinese astronomers as a new or "guest star," and was about four times brighter than Venus, or about mag -6. According to the records, it was visible in daylight for 23 days, and 653 days to the naked eye in the night sky. It was probably also recorded by Anasazi Indian artists (in present-day Arizona and New Mexico), as findings in Navaho Canyon and White Mesa (both Arizona) as well as in the Chaco Canyon National Park (New Mexico) indicate; there's a review of the research on the Chaco Canyon Anasazi art online. In addition, Ralph R. Robbins of the University of Texas has found Mimbres Indian art from New Mexico, possibly depicting the supernova.

The Supernova 1054 was also assigned the variable star designation CM Tauri. It is one of few historically observed supernovae in our Milky Way Galaxy.

The nebulous remnant was discovered by John Bevis in 1731, who added it to his sky atlas, Uranographia Britannica. Charles Messier independently found it on August 28, 1758, when he was looking for comet Halley on its first predicted return, and first thought it was a comet. Of course, he soon recognized that it had no apparent proper motion, and cataloged it on September 12, 1758. It was the discovery of this object which caused Charles Messier to begin with the compilation of his catalog. It was also the discovery of this object, which closely resembled a comet (1758 De la Nux, C/1758 K1) in his small refracting telescope, which brought him to the idea to search for comets with telescopes (see his note). Messier acknowledged the prior, original discovery by Bevis when he learned of it in a letter of June 10, 1771.

Although Messier's catalog was primarily compiled for preventing confusion of these objects with comets, M1 was again confused with comet Halley on the occasion of that comet's second predicted return in 1835.

This nebula was christened the "Crab Nebula" on the ground of a drawing made by Lord Rosse about 1844. Of the early observers, Messier, Bode and William Herschel correctly remarked that this nebula is not resolvable into stars, but William Herschel thought that it was a stellar system which should be resolvable by larger telescopes. John Herschel and Lord Rosse erroneously thought it is "barely resolvable" into stars. They and others, including Lassell in the 1850s, apparently mistook filamentary structures as indication for resolvability.

Early spectroscopic observations, e.g. by Winlock, revealed the gaseous nature of this object in the later 19th century. The first photo of M1 was obtained in 1892 with a 20-inch telescope. First serious investigations of its spectrum were performed in 1913-15 by Vesto M. Slipher (Slipher 1915, 1916): He found that the spectral emission lines were split. It was later recognised that the true reason for this is Doppler shift, as parts of the nebula are approaching us (thus their lines are blueshifted) and others receding from us (lines redshifted). In 1919, Roscoe Frank Sanford (Sanford 1919) found that the spectrum consists of two major contributions: First, a reddish component which forms a chaotic web of bright filaments, which has an emission line spectrum (including hydrogen lines) like that of diffuse gaseous (or planetary) nebulae, and second a strong blueish diffuse background which has a continuous spectrum.

Heber D. Curtis, in his description of this object based on Lick Observatory photographs, tentatively classified it as a planetary nebula (Curtis 1918), a view which was disproved only in 1933; this mis-classification can still be found in some much newer handbooks.

In 1921, C.O. Lampland of Lowell Observatory, when comparing excellent photographs of the nebula obtained with their 42-inch reflector, found notable motions and changes, also in brightness, of individual components of the nebula, including dramatic changes of some patches near the central pair of stars (Lampland 1921). The same year, J.C. Duncan of Mt. Wilson Observatory compared photographic plates taken 11.5 years apart, and found that the Crab Nebula was expanding at an average of about 0.2" per year; backtracing of this motion showed that this expansion must have begun about 900 years ago (Duncan 1921). Also the same year, Knut Lundmark noted the proximity of the nebula to the 1054 supernova (Lundmark 1921).

In 1942, based on investigations with the 100-inch Hooker telescope on Mt. Wilson, Walter Baade computed a more acurate figure of 760 years age from the expansion, which yields a starting date around 1180 (Baade 1942); later investigations improved this value to about 1140. The actual 1054 occurrance of the supernova shows that the expansion must have been accelerated.

The nebula consists of the material ejected in the supernova explosion, which has been spread over a volume approximately 10 light years in diameter, and is still expanding at the very high velocity of about 1,800 km/sec. The notion of gaseous filaments and a continuum background was photographically confirmed by Walter Baade and Rudolph Minkowski in 1930: The filaments are apparently the remnants from the former outer layers of the former star (the "pre-supernova" or supernova "progenitor"), while the inner, blueish nebula emits continuous light consisting of highly polarised so-called synchrotron radiation, which is emitted by high-energy (fast moving) electrons in a strong magnetic field. This explanation was first proposed by the Soviet astronomer J. Shklovsky (1953) and supported by observations of Jan H. Oort and T. Walraven (1956).

Synchrotron radiation is also apparent in other "explosive" processes in the cosmos, e.g. in the active core of the irregular galaxy M82 and the peculiar jet of giant elliptical galaxy M87. These striking properties of the Crab Nebula in the visible light are equally conspicuous in the Palomar images post-processed by David Malin of the Anglo Australian Observatory, and in Paul Scowen's image obtained on Mt. Palomar.

In 1949, the Crab nebula was identified as a strong source of radio radiation (Bolton et.al. 1949), discovered 1948 named and listed as Taurus A (Bolton 1948), and later as 3C 144. X-rays from this object were detected in April 1963 with a high-altitude rocket of type Aerobee with an X-ray detector developed at the Naval Research Laboratory; the X-ray source was named Taurus X-1. Measurements during lunar occultations of the Crab Nebula on July 5, 1964, and repeated in 1974 and 1975, demonstrated that the X-rays come from a region at least 2 arc minutes in size, and the energy emitted in X-rays by the Crab nebula is about 100 times more than that emitted in the visual light. Nevertheless, even the luminosity of the nebula in the visible light is enormous: At its distance of 6,300 light years (which is quite well-determined, by Virginia Trimble (1973)), its apparent brightness corresponds to an absolute magnitude of about -3.2, or more than 1000 solar luminosities. Its overall luminosity in all spectral ranges was estimated at 100,000 solar luminosities or 5*10^38 erg/s !

On November 9, 1968, a pulsating radio source, the Crab Pulsar (also cataloged as NP0532, "NP" for NRAO Pulsar, or PSR 0531+21), was detected in M1 by astronomers of the Arecibo Observatory 300-meter radio telescope in Puerto Rico. This star is the right (south-western) one of the pair visible near the center of the nebula in our photo. This pulsar was the first one which was also verified in the optical part of the spectrum, when W.J. Cocke, M.J. Disney and D.J. Taylor of Steward Observatory, Tucson, Arizona found it flashing at the same period of 33.085 milliseconds as the radio pulsar with the 90-cm (36-inch) telescope on Kitt peak; this discovery happened on January 15, 1969 at 9:30 pm local time (January 16, 1969, 3:30 UT, according to Simon Mitton). This optical pulsar is sometimes also referred to by the supernova's variable star designation, CM Tauri.

Only in 2007, it came to light that months before the detection of the Crab Pulsar - end even the first pulsar ever discovered - this object had been found in summer 1967, by US Air Force officer Charles Schisler on duty. Charles was on radar duty at Clear USAFB Alaska in summer 1967, when he noticed and logged a fluctuating radio source which was not moving, i.e. at fixed RA and Dec. The next day it was there again, and when he determined its position, he identified it with the Crab Nebula. Subsequently, he found a number of further pulsars. However, USAF decided that this was not their business, and didn't publish his findings. Therefore, Joycelyn Bell independently found her first pulsar a couple of months later.

It has now been established that this pulsar is a rapidly rotating neutron star: It rotates about 30 times per second! This period is very well investigated because the neutron star emits pulses in virtually every part of the electromagnetic spectrum, from a "hot spot" on its surface. The neutron star is an extremely dense object, denser than an atomic nucleus, concentrating more than one solar mass in a volume of 30 kilometers across. Its rotation is slowly decelerating by magnetic interaction with the nebula; this is now a major energy source which makes the nebula shining; as stated above, this energy source is 100,000 times more energetic than our sun.

In the visible light, the pulsar is of 16th apparent magnitude. This means that this very small star is roughly of absolute magnitude +4.5, or about the same luminosity as our sun in the visible part of the spectrum !

Jeff Hester and Paul Scowen have used the Hubble Space Telescope to investigate the Crab Nebula M1 (see also e.g. Sky & Telescope of January, 1995, p. 40). Their continuous investigations with the HST have provided new insight into the dynamic and changes of the Crab nebula and pulsar. More recently, the Heart of the Crab was investigated by HST astronomers.

This object has attracted so much interest that it was remarked that astronomers can be devided into two fractions of about same size: Those who do work related to the Crab nebula, and those who don't. There was a "Crab Nebula Symposium" in Flagstaff, Arizona in June, 1969 (see PASP Vol. 82, May 1970 for results - Burnham). The IAU symposium No. 46, held at Jodrell Bank (England) in August 1970 was solely devoted to this object. Simon Mitton has written a nice book on the Crab Nebula M1 in 1978, which is still most readable and informative (it is also source for some of the informations here).

The Crab Nebula can be found quite easily from Zeta Tauri (or 123 Tauri), the "Southern Horn" of the Bull, a 3rd-magnitude star which can be easily found ENE of Aldebaran (Alpha Tauri). M1 is about 1 deg N and 1 deg W of Zeta, just slightly south and about 1/2 degree west of a mag-6 star, Struve 742.

The nebula can be easily seen under clear dark skies, but can equally easily get lost in the background illumination under less favorable conditions. M1 is just visible as a dim patch in 7x50 or 10x50 binoculars. With a little more magnification, it is seen as a nebulous oval patch, surrounded by haze. In telescopes starting with 4-inch aperture, some detail in its shape becomes apparent, with some suggestion of mottled or streak structure in the inner part of the nebula; John Mallas reports that under excellent conditions, an experienced observer can see them throughout the inner portion of the nebula. The amateur can verify Messier's impression that M1 looks indeed similar to a faint comet without tail in smaller instruments. Only under excellent conditions and with larger telescopes, starting at about 16 inches aperture, suggestions of the filaments and fine structure may become visible.

As the Crab Nebula is situated only 1 1/2 degrees from the ecliptic, there are frequent conjunctions and occasional transits of planets, as well as occultations by the Moon (some of them mentioned above).

M1 is situated in a nice Milky Way field. The star Zeta Tauri is remarkable as it is a Gamma Cassiopeiae type variable, a rather rapidly rotating star of spectral type B4 III pe which has ejected an expanding gas shell, and has a fainter spectroscopic companion star in an orbit of about 133 days period. Preceding M1 two minutes (or half a degree) in Right Ascension is Struve 742 or ADS 4200, another visual binary star with components A (mag 7.2, spectrum F8, of yellow color) and B (mag 7.8, white) separated by about 3.6" in position angle 272deg, and orbiting each other in about 3000 years.

m008_lagoon_avg_200percent_ps-um-lvl.jpg

m008_lagoon_avg_200percent_ps-um-lvl.jpg (m008_lagoon_avg_200percent_ps-um-lvl.jpg)

M8 - The Lagoon Nebula.

This is right near the heart of the Milky Way from our vantage point in Sagatarius. It is actually a naked eye object. This image was taken with the 30" f/4.8 Challenger observatory scope at Fremont Peak and Canon 20D.

Messier 8

Starforming Nebula M8 (NGC 6523), an emission nebula, with open star cluster, type "e", in Sagittarius

Lagoon Nebula

Right Ascension 18 : 03.8 (h:m)

Declination -24 : 23 (deg:m)

Distance 5.2 (kly)

Visual Brightness 6.0 (mag)

Apparent Dimension 90x40 (arc min)

Discovered by Hodierna about 1654.

Excerpt from seds.org:

The Lagoon Nebula Messier 8 (M8, NGC 6523) is one of the finest and brightest star-forming regions in the sky. It is a giant cloud of interstellar matter which is currently undergoing vivid star formation, and has already formed a considerable cluster of young stars.

This object has been discovered by Giovanni Battista Hodierna before 1654, and classified it as "nebulosa," i.e. of intermediate brightness; it is his No. II.6. It was independently noted as a "nebula" by John Flamsteed about 1680, who cataloged it as his No. 2446. Due to reasons which are not completely clear, at least to the present author [hf], Kenneth Glyn Jones has supposed that Flamsteed may only have seen the cluster within this nebula, a view which we had formerly adopted here. However, Flamsteed's position is close to that later determined by Messier and near the center of the nebula, while the young open cluster, which was later cataloged as NGC 6530, is situated (or at least centered) in the Eastern half of M8.

This object was again seen by Philippe Loys de Chéseaux in 1746, who could resolve some stars and consequently classified it as a cluster. One year later, in 1747, it was observed by Guillaume Le Gentil, who found the nebula together with the cluster. Abbe Nicholas Louis de la Caille has cataloged it in his 1751-52 compilation as Lacaille III.14. When Charles Messier cataloged this object on May 23, 1764, he primarily described the cluster, and mentioned the nebula separately as surrounding the star 9 Sagittarii; his original position is closer to the modern position of the cluster than to that of the nebula. Nevertheless, until recently, most sources identified only the nebula with "Messier 8," a view we reject here: It is clear from Messier's description that he had found both the nebula and the cluster.

William Herschel assigned separate catalog numbers to two objects within, or parts of, the Lagoon Nebula: H V.9 (GC 4363, NGC 6526) and H V.13 (GC 4368, NGC 6533) which are described as large and faint nebulae in the NGC. John Herschel eventually cataloged the open cluster NGC 6530 separately as h 3725 (GC 4366); he has M8 as h 3723 (GC 4361, NGC 6523).

According to Kenneth Glyn Jones, the Lagoon Nebula has an apparent extension of 90x40 minutes of arc, which is 3 x 1 1/3 the apparent diameter of the full moon, and corresponds to about 140x60 light years if our distance of 5,200 light years should be correct, which is a bit uncertain; newer sources have 4850 (Glyn Jones) to 6500, but David J. Eichler gives the value of 5,200 light years (Eichler 1996).

One of the remarkable features of the Lagoon Nebula is the presence of dark nebulae known as 'globules' (Burnham) [see expanded image] which are collapsing protostellar clouds with diameters of about 10,000 AU (Astronomical Units). They can also be seen, along with other detail, in the DSSM image of M8. Some of the more conspicuous globules have been cataloged in E.E. Barnard's catalog of dark nebulae: Barnard 88 (B 88), the comet-shaped globule extended North-to-South (up-down) in the left half and near top of our image, small B 89 in the region of cluster NGC 6530, and long, narrow black B 296 at the south edge of the nebula (lower edge of the image). According to David Eichler, the nebula has probably a depth comparable to its linear extension indicated above.

Within the brightest part of the Lagoon Nebula, a remarkable feature can be seen, which according to its shape is called the "Hourglass Nebula" (see our detailed photos). This feature was discovered by John Herschel and occurs in a region where a vivid star formation process appears to take place currently; the bright emission is caused by heavy excitation of very hot, young stars, the illuminator of the hourglass is the hot star Herschel 36 (mag 9.5, spectral class O7). Closely by this feature is the apparently brightest of the stars associated with the Lagoon Nebula, 9 Sagittarii (mag 5.97, spectral class O5), which surely contributes a lot of the high energy radiation which excites the nebula to shine.

As published in January 1997, the Hubble Space Telescope has been used to study the Hourglass Nebula region in the Lagoon Nebula M8.

The Lagoon Nebula is a magnificient object for the amateur astrophotographer, as Brad Wallis and Robert Provin have demonstrated with their outstanding images, and Dr. Andjelko Glivar with his photos taken through a Celestron 8.

The young open cluster NGC 6530 associated with the Lagoon Nebula M8 was classified as of Trumpler type "II 2 m n" (see e.g. the Sky Catalog 2000), meaning that it is detached but only weakly concentrated toward its center, its stars scatter in a moderate range of brightness, it is moderately rich (50--100 stars), and associated with nebulosity (certainly, with the Lagoon nebula). As the light of its member stars show little reddening by interstellar matter, this cluster is probably situated just in front of the Lagoon Nebula. Its brightest star is a 6.9 mag hot O5 star, and Eichler gives its age as 2 million years. Woldemar Götz mentions this cluster as containing one peculiar Of star, an extremely hot bright star of spectral type O with peculiar spectral lines of ionized Helium and Nitrogen.

The nebula's faint extension to the East (top in our image, but beyond) has an own IC number: IC 4678.

M8 is situated in a very conspicuous field of the Sagittarius Milky Way. Another capture from the DSSM shows the Lagoon Nebula M8 and Trifid Nebula M20, plus the rich star field and faint nebulae surrounding them. We have also more images of the region of M8 and M20, which sometimes also include the nearby open star cluster M21.

m013_127mmf121_20d-nr_300seciso1600_000002_ip-ddp4122-statdiff1515-addbal_5299-6189_0922.jpg

m013_127mmf121_20d-nr_300seciso1600_000002_ip-ddp4122-statdiff1515-addbal+5299-6189+0922.jpg (m013_127mmf121_20d-nr_300seciso1600_000002_ip-ddp4122-statdiff1515-addbal+5299-6189+0922.jpg)

M13 - Hercules Cluster. A single 5min exposure with in-cam noise reduction at 1600 iso from backyard in the bay area. The scope was a friend's 127mm f/12.1 Orion MakCas. Nice little scope. The seeing was exceptionaly that night.  M013_DSI2PRO_09C_CLEAR_13x300sec_ip-adpadd.jpg

M013_DSI2PRO+09C_CLEAR_13x300sec_ip-adpadd.jpg Enter image description for image (M013_DSI2PRO+09C_CLEAR_13x300sec_ip-adpadd.jpg)

M13 taken with DSI2 and 10" f/10 Meade classic OTA on AP1200 mount. 9C sensor temp on DSI 2 Pro

13x5min exposures.

Note small galaxy at the top.

M13 is call the Hercules Cluster because it is in the constellation Hercules. It is very large and it can be seen with binoculars as a fuzzy object.

Messier 13

Globular Cluster M13 (NGC 6205), class V, in Hercules

Hercules Globular Cluster

Right Ascension 16 : 41.7 (h:m)

Declination +36 : 28 (deg:m)

Distance 25.1 (kly)

Visual Brightness 5.8 (mag)

Apparent Dimension 20.0 (arc min)

Discovered by Edmond Halley in 1714.

Excerpt from seds.org:

Messier 13 (M13, NGC 6205), also called the 'Great globular cluster in Hercules', is one of the most prominent and best known globulars of the Northern celestial hemisphere.

It was discovered by Edmond Halley in 1714, who noted that 'it shows itself to the naked eye when the sky is serene and the Moon absent.' According to Charles Messier, who cataloged it on June 1, 1764, it is also reported in John Bevis' "English" Celestial Atlas.

At its distance of 25,100 light years, its angular diameter of 20' corresponds to a linear 145 light years - visually, it is perhaps 13' large. It contains several 100,000 stars; Timothy Ferris in his book Galaxies even says "more than a million". Towards its center, stars are about 500 times more concentrated than in the solar neighborhood. The age of M13 has been determined by Sandage as 24 billion years and by Arp as 17 billion years around 1960; Arp later (in 1962) revised his value to 14 billion years (taken from Kenneth Glyn Jones).

According to Kenneth Glyn Jones, M13 is peculiar in containing one young blue star, Barnard No. 29, of spectral type B2. The membership of this star was confirmed by radial velocity measurement, and is strange for such an old cluster - apparently it is a captured field star.

Observers note 4 apparently star-poor regions in M13 (e.g., Mallas). Suggestions of them can be noted in some photos.

Globular cluster M13 was selected in 1974 as target for one of the first radio messages addressed to possible extra-terrestrial intelligent races, and sent by the big radio telescope of the Arecibo Observatory.

Nearby, about 40 arc minutes north-east of M13, is the faint (mag 11) galaxy NGC 6207, visible in many large- and medium-size-field photographs of M13, e.g., in the DSSM image. This galaxy has recently produced a type II supernova (SN 2004A).

m016_adpadd26_ps_umask.jpg

m016_adpadd26_ps_umask.jpg (m016_adpadd26_ps_umask.jpg)

M16 - Eagle Nebula and the Pinnacles of Life

This was an elusive target for me. I could never really get the pinnacles with the resulution I should have with the 12" SCT. This image was a stack of 26 3min stops at 1600 iso taken at Fremont Peak.

Messier 16

Starforming Nebula M16 (IC 4703, NGC 6611), an emission nebula, with Open Star Cluster, type 'e', in Serpens (Cauda)

Eagle Nebula

Right Ascension 18 : 18.8 (h:m)

Declination -13 : 47 (deg:m)

Distance 7.0 (kly)

Visual Brightness 6.4 (mag)

Apparent Dimension 7.0 (arc min)

Excerpt from seds.org:

Cluster M16 (NGC 6611) discovered by Philippe Loys de Chéseaux in 1745-6.

Nebula M16 (IC 4703) discovered by Charles Messier in 1764.

The Eagle Nebula Messier 16 (M16) is a conspicuous region of active star formation, situated in Serpens Cauda. The starforming nebula, a giant cloud of interstellar gas and dust, has already created a considerable cluster of young stars. The cluster is also referred to as NGC 6611, the nebula as IC 4703.

The discoverer, Philippe Loys de Chéseaux, describes only the cluster when recording his 1745-1746 discovery. Charles Messier, on his independent rediscovery of June 3, 1764, mentions that these stars appeared "enmeshed in a faint glow", probably suggestions of the nebula. The Herschels apparently didn't perceive the nebula, so that their catalogs and consequently, the NGC, only describe the cluster. The nebula was added in the IC II of 1908 as IC 4703, with "cluster M16 involved", but the NGC 2000.0 erroneously classifies this object as an open cluster.

The nebula was probably first photographed by E.E. Barnard in 1895, and by Isaac Roberts in 1897; Isaac Robert's finding brought this object into the IC catalog.

Lying some 7,000 light years distant in the constellation Serpens, close to the borders to Scutum and Sagittarius, and in the next inner spiral arm of the Milky Way galaxy from us (the Sagittarius or Sagittarius-Carina Arm) a great cloud of interstellar gas and dust has entered a vivid process of star formation. Open star cluster M16 has formed from this great gaseous and dusty cloud, the diffuse Eagle Nebula IC 4703, which is now caused to shine by emission light, excited by the high-energy radiation of its massive hot, young stars. It is actually still in the process of forming new stars, this formation taking place near the dark "elephant trunks" which are well visible in our photograph, as well as in AAT pictures and other images of M16. A deeper insight in the star formation process could be obtained from the HST images of M16, published in November 1995; moreover, they were used for an animation simulating the approach to this star forming region, and we provide some screen sized images (suitable as backgrounds for your computer screen).

This stellar swarm is only about 5.5 million years old (according to the Sky Catalog 2000 and Götz) with star formation still active in the Eagle Nebula; this results in the presence of very hot young stars of spectral type O6. The cluster was classified as of Trumpler type II,3,m,n (Götz). The brightest star of M16 is of visual magnitude 8.24. At its distance of 7,000 light years, its angular diameter of 7 arc minutes corresponds to a linear extension of about 15 light years. The nebula extends much farther out, to a diameter of over 30', corresponding to a linear size of about 70x55 light years.

Some sources have smaller distances for M16: Kenneth Glyn Jones gives 5,870. Götz 5,540 light years. Götz states that this is one of the intrinsically most luminous open clusters, at an absolute magnitude of -8.21.

M16 is found rather easily, either by locating the star Gamma Scuti, a white giant star of magnitude 4.70 and spectral type A2 III, e.g. from Altair (Alpha Aquilae) via Delta and Lambda Aql; M16 is about 2 1/2 deg (19 min in RA) west of this star. Or, in particular with a pair of binoculars, locate star cloud M24, and move northward via a pair of stars of 6th and 7th mag, followed by small open cluster M18 1deg North of M24, the magnificient Omega Nebula M17 another 1deg N, and finally another 2deg N, M16.

Star cluster M16 and the Eagle Nebula are best seen with low powers in telescopes. A 4-inch reveals about 20 stars in an uneven background of fainter stars and nebulosity; three nebulous concentrations can be glimpsed under good observing conditions. Under very good conditions, suggestions of dark obscuring matter can be seen to the north of the cluster. The Eagle nebula is best seen on photographs, but larger apertures and nebula filters (O-III) may help to trace some detail visually. The dark pillars can be seen in large amateur instruments (12-inch up).

m020_trifidnebulain3d.jpg

m020_trifidnebulain3d.jpg (m020_trifidnebulain3d.jpg)

If you stare at this image, you get a false sense of 3D. Some stars seem to be up front and some farther away. It is a cheesy experiment but kind of fun in the process.  (m020avg4_ps2.c.jpg)

M20 - Trifid Nebula

Image taken with 764mm (30") f/4.8 FPOA Challenger observatory scope.

The Trifid Nebula gets its name from the three main "petals" in this flower shaped nebula. There are actually four such petals, but only three were visible when it got its name, hense the "tri" part of its name. This nebula has lots of blue reflection nebula component to it, where as the nearby M8 Lagoon Nebula is different.

Messier 20

Starforming Nebula M20 (NGC 6514), an emission and reflection nebula, with Open Star Cluster, in Sagittarius

Trifid Nebula

Right Ascension 18 : 02.6 (h:m)

Declination -23 : 02 (deg:m)

Distance 5.2 (kly)

Visual Brightness 9.0 (mag)

Apparent Dimension 28.0 (arc min)

Discovered by Charles Messier in 1764.

Excerpt from seds.org:

The Trifid Nebula Messier 20 (M20, NGC 6514) in Sagittarius is a remarkable and beautiful object as it consists of both a conspicuous emission nebula and a remarkable reflection nebula component.

Charles Messier discovered this object on June 5, 1764, and described it as a cluster of stars of 8th to 9th magnitude, enveloped in nebulosity, where the remark on nebulosity follows only after the description of nearby M21, and includes that object.

The Trifid Nebula M20 is famous for its three-lobed appearance. This may have caused William Herschel, who normally carefully avoided to number Messier's objects in his catalog, to assign four different numbers to parts of this nebula: H IV.41 (cataloged May 26, 1786) and H V.10, H V.11, H V.12 (dated July 12, 1784). That he numbered this object at all may have its reason in the fact that Messier merely described it as 'Cluster of Stars.' The name 'Trifid' was first used by John Herschel to describe this nebula; this astronomer assigned only one catalog entry to the whole object (h 1991, h 3718, GC 4355) which became J.L.E. Dreyer's NGC 6514.

The dark nebula, which is the reason for the Trifid's appearance, was cataloged by Barnard as Barnard 85 (B 85).

The red emission nebula with its young star cluster near its center is surrounded by a blue reflection nebula which is particularly conspicuous to the northern end. The nebula's distance is rather uncertain, with values between 2,200 light years (Mallas/Kreimer; Glyn Jones has 2,300) and about 7,600 light years (C.R. O'Dell 1963). The Sky Catalog 2000 gives 5,200 light years, a value which is also used by Archinal and Hynes (2003), and which we adopt here. The WEBDA database has 3140, the Hubble Press Release of Jeff Hester (STScI-PRC99-42) gives "about 9000" light years.

As often for nebulae, magnitude estimates spread widely: Kenneth Glyn Jones gives 9.0, while Machholz has estimated 6.8 mag. This may partly come from the fact that the exciting star, HD 196692 or HN 40 or ADS 10991, is a triple system of 7th integrated magnitude (with components A: 7.6, B: 10.7, C: 8.7 mag). All are extremely hot; component A is of spectral type O5 to O7. The Sky Catalogue 2000.0 even lists 4 more, faint components of this "multiple star:" D: 10.7, E: 12.6, F: 14.0, and G: 13.4 mag. This star is located on the west side of the Trifid Nebula cluster. Situated on the northern edge is HD 164514 of visual magnitude 7.42, a supergiant of spectral type A5 Ia. The presence of these considerably bright stars makes brightness estimates for the nebula difficult.

In the sky, the Trifid nebula M20 is situated roughly 2 degrees northwest of the larger Lagoon Nebula M8, so that both nebulae form a nice target for wide field photographs, as these images of the M8 and M20 region, or the big DSSM image of this region. It is even closer to the open cluster M21 and shows up in the upper left edge of our M21 image.

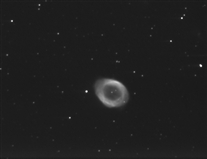

m027_ed80f075_20d-nr_60seciso1600_ip-ddp11416.jpg

m027_ed80f075_20d-nr_60seciso1600_ip-ddp11416.jpg (m027_ed80f075_20d-nr_60seciso1600_ip-ddp11416.jpg)

M27 - Dumbell Nebula

Orion ED80 f/7.5 with Canon 20D - incamera noise reduction. Single 60sec exposure at 1600iso.

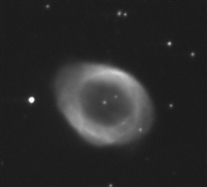

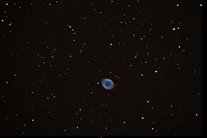

m027dumbellnebadpadd27_ip-ddh.cropped1024.jpg

m027dumbellnebadpadd27_ip-ddh.cropped1024.jpg (m027dumbellnebadpadd27_ip-ddh.cropped1024.jpg)

M27 - Dumbell Nebula

This was taken with the 764mm f/4.8 Challenger observatory scope. It is a stack of 27 images at about 1-2min each.

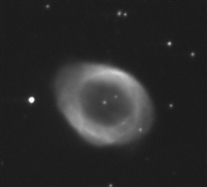

Messier 27

Planetary Nebula M27 (NGC 6853), type 3a+2, in Vulpecula

Dumbbell Nebula

Right Ascension 19 : 59.6 (h:m)

Declination +22 : 43 (deg:m)

Distance 1.25 (kly)

Visual Brightness 7.4 (mag)

Apparent Dimension 8.0x5.7 (arc min)

Discovered by Charles Messier in 1764.

Excerpt from seds.org:

The Dumbbell Nebula Messier 27 (M27, NGC 6853) is perhaps the finest planetary nebula in the sky, and was the first planetary nebula ever discovered.

On July 12, 1764, Charles Messier discovered this new and fascinating class of objects, and describes this one as an oval nebula without stars. The name "Dumb-bell" goes back to the description by John Herschel, who also compared it to a "double-headed shot."

We happen to see this one approximately from its equatorial plane (approx. left-to-right in our image); this is similar to our view of another, fainter Messier planetary nebula, M76, which is called the Little Dumbbell. From near one pole, it would probably have the shape of a ring, and perhaps look like we view the Ring Nebula M57.

This planetary nebula is certainly the most impressive object of its kind in the sky, as the angular diameter of the luminous body is nearly 6 arc minutes, with a faint halo extensing out to over 15', half the apparent diameter of the Moon (Millikan 1974). It is also among the brightest, being at most little less luminous with its estimated apparent visual magnitude 7.4 than the brightest, the Helix Nebula NGC 7293 in Aquarius, with 7.3, which however has a much lower surface brightness because of its larger extension (estimates from Stephen Hynes); it is a bit unusual that this planetary is only little fainter photographically (mag 7.6). The present author (hf) was surprized how fine this object was seen in his 10x50 binoculars under moderately good conditions !

As measured by Soviet astronomer O.N. Chudowitchera from Pulkowo (and mentioned by L.H. Aller, Glyn Jones and Vehrenberg), the bright portion of the nebula is apparently expanding at a rate of 6.8 arc seconds per century, leading to an estimated age of 3,000 to 4,000 years, i.e. the shell ejection probably would have been observable this time ago (it actually happened earlier as the light had to travel all the distance of perhaps about 1000 light years). She estimated the distance somewhat short at only about 490 ly. Another estimate, given by Burnham, has obtained a rate 1.0 arc seconds per century, and an estimated age of 48,000 years.

The central star of M27 is quite bright at mag 13.5, and an extremely hot blueish subdwarf dwarf at about 85,000 K (so the spectral type is given as O7 in the Sky Catalog 2000). K.M. Cudworth of the Yerkes Observatory found that it probably has a faint (mag 17) yellow companion at 6.5" in position angle 214 deg (Burnham).

As for most planetary nebulae, the distance of M27 (and thus true dimension and intrinsic luminosity) is not very well known. Hynes gives about 800, Kenneth Glyn Jones 975, Mallas/Kreimer 1250 light years, while other existing estimates reach from 490 to 3500 light years. Currently, investigations with the Hubble Space Telescope are under work to determine a more reliable and acurate value for the distance of the Dumbbell Nebula.

Adopting our value of 1200 light years, the intrinsic luminosity of the gaseous nebula is about 100 times that of the Sun (about -0.5 Mag absolute) while the star is at about +6 (1/3 of the Sun) and the companion at +9..9.5 (nearly 100 times fainter than the Sun), all in the visual light part of the electromagnetic spectrum. That the nebula is so much brighter than the star shows that the star emits primarily highly energetic radiation of the non-visible part of the electro-magnetic spectrum, which is absorbed by exciting the nebula's gas, and re-emitted by the nebula, at last to a good part in the visible light. Actually, as for almost all planetary nebulae, most of the visible light is even emitted in one spectral line only, in the green light at 5007 Angstrom (see our planetary nebula description) !

By comparing images of the Dumbbell Nebula M27, Leos Ondra has discovered a variable star situated in the very outskirts of the nebula which he called Goldilocks' Variable. This variable can be found in some of our images, namely those of Jack Newton, Peter Sütterlin and (faintly) David Malin's INT photo, as well as one of the images by John Sefick. Other images such as the one in this page don't show this star, proving its variability.

About 2deg to the West of M27 is inconspicuous open cluster NGC 6830, containing about 20-30 widely scattered stars; this cluster is about 5500 ly distant.

m031_57deg_ed80f075_20d_800iso_10x300sec_sigmed_ps-lvl-curve-usm.jpg

m031_57deg_ed80f075_20d_800iso_10x300sec_sigmed_ps-lvl-curve-usm.jpg (m031_57deg_ed80f075_20d_800iso_10x300sec_sigmed_ps-lvl-curve-usm.jpg)

M31 - The Great Andromeda Galaxy. M32 and M110 are also visible in this image.

Orion ED80 f/7.5, canon 20D, 800 iso. 10 x 5min exposures stacked in Images Plus 2.83. Prettied up in photoshop.

M31 is about 2.4 million light years away and it is the most distant object viewable with the naked eye. Our Milky Way galaxy is falling toward M31 at nearly 1 million miles per hour.

Messier 31

Spiral Galaxy M31 (NGC 224), type Sb, in Andromeda

Andromeda Galaxy

Right Ascension 00 : 42.7 (h:m)

Declination +41 : 16 (deg:m)

Distance 2900 (kly)

Visual Brightness 3.4 (mag)

Apparent Dimension 178x63 (arc min)

Known to Al-Sufi about AD 905.

Excerpt from seds.org:

Messier 31 (M31, NGC 224) is the famous Andromeda galaxy, our nearest large neighbor galaxy, forming the Local Group of galaxies together with its companions (including M32 and M110, two bright dwarf elliptical galaxies), our Milky Way and its companions, M33, and others.

Visible to the naked eye even under moderate conditions, this object was known as the "little cloud" to the Persian astronomer Abd-al-Rahman Al-Sufi, who described and depicted it in 964 AD in his Book of Fixed Stars: It must have been observed by and commonly known to Persian astronomers at Isfahan as early as 905 AD, or earlier. R.H. Allen (1899/1963) reports that it was also appeared on a Dutch starmap of 1500. Charles Messier, who cataloged it on August 3, 1764, was obviously unaware of this early reports, and ascribed its discovery to Simon Marius, who was the first to give a telescopic description in 1612, but (according to R.H. Allen) didn't claim its discovery. Unaware of both Al Sufi's and Marius' discovery, Giovanni Batista Hodierna independently rediscovered this object before 1654. Edmond Halley, however, in his 1716 treat of "Nebulae", accounts the discovery of this "nebula" to the French astronomer Bullialdus (Ismail Bouillaud), who observed it in 1661; but Bullialdus mentions that it had been seen 150 years earlier (in the early 1500s) by some anonymous astronomer (R.H. Allen, 1899/1963).

It was longly believed that the "Great Andromeda Nebula" was one of the nearest nebulae. William Herschel believed, wrongly of course, that its distance would "not exceed 2000 times the distance of Sirius" (17,000 light years); nevertheless, he viewed it at the nearest "island universe" like our Milky Way which he assumed to be a disk of 850 times the distance of Sirius in diameter, and of a thickness of 155 times that distance.

It was William Huggins, the pioneer of spectroscopy, who noted in 1864 the difference between gaseous nebula with their line spectra and those "nebulae" with star-like, continuous spectra, which we now know as galaxies, and found a continuous spectrum for M31 (Huggins and Miller 1864).

In 1887, Isaac Roberts obtained the first photographs of the Andromeda "Nebula," which showed the basic features of its spiral structure for the first time.

In 1912, V.M. Slipher of Lowell Observatory measured the radial velocity of the Andromeda "nebula" and found it the highest velocity ever measured, about 300 km/sec in approach. This already pointed to the extra-galactic nature of this object. According to Burnham, a better value is about 266 km/sec, but R. Brent Tully gives 298 km/sec, and NED has again 300 +/- 4 km/s as the modern value. Note that all the previous values describe the motion with respect to our Solar System, i.e. heliocentric motion, not that w.r.t. the Milky Way's Galactic Center. The latter value can be obtained by correcting for the motion of our Solar System around that center. The modern values for Galactic rotation and heliocentric radial velocity yield that the Andromeda Galaxy and the Milky Way are approaching each other at about 100 km/sec.

In 1923, Edwin Hubble found the first Cepheid variable in the Andromeda galaxy and thus established the intergalactic distance and the true nature of M31 as a galaxy. Because he was not aware of the two Cepheid classes, his distance was incorrect by a factor of more than two, though. This error was not discovered until 1953, when the 200-inch Palomar telescope was completed and had started observing. Hubble published his epochal study of the Andromeda "nebula" as an extragalactic stellar system (galaxy) in 1929 (Hubble 1929).

At modern times, the Andromeda galaxy is certainly the most studied "external" galaxy. It is of particular interest because it allows studies of all the features of a galaxy from outside which we also find in Milky Way, but cannot observe as the greatest part of our Galaxy is hidden by interstellar dust. Thus there are continuous studies of the spiral structure, globular and open clusters, interstellar matter, planetary nebulae, supernova remnants (see e.g. Jeff Kanipe's article in Astronomy, November 1995, p. 46), galactic nucleus, companion galaxies, and more.

Some of the features mentioned above are also of interest for the amateur: Even Charles Messier found its two brightest companions, M32 and M110 which are visible in binoculars and conspicuous in small telescopes, and created a drawing of all three. These two relatively bright and relatively close companions are visible in many photos of M31, including the one in this page. They are only the brightest of a "swarm" of smaller companions which surround the Andromeda Galaxy, and form a subgroup of the Local Group. At the time of this writing (September 2003), at least 11 of them are known: Besides M32 and M110 these are NGC 185, which was discovered by William Herschel, and NGC 147 (discovered by d'Arrest) as well as the very faint dwarf systems And I, And II, And III, possibly And IV (which may however be a cluster or a remote background galaxy), And V, And VI (also called the Pegasus dwarf), And VII (also Cassiopeia dwarf), and And VIII. It is still not clear if M33, the smaller spiral galaxy in Triangulum, and its probable companion LGS 3 belong to this subgroup, or the more remote Local Group member IC 1613, or one of the possible member candidates UGCA 86 or UGCA 92.

The Andromeda Galaxy is in notable interaction with its companion M32, which is apparently responsible for a considerable amount of disturbance in the spiral structure of M31. The arms of neutral hydrogen are displaced from those consisted of stars by 4000 light years, and cannot be continuously followed in the area closest to its smaller neighbor. Computer simulations have shown that the disturbances can be modelled by a recent close encounter with a small companion of the mass of M32. Very probably, M32 has also suffered from this encounter by losing many stars which are now spread in Andromeda's halo.

The brightest globular cluster of the Andromeda Galaxy M31, G1, is also the most luminous globular in the Local Group of Galaxies; its apparent visual brightness from Earth is still about 13.72 magnitudes. It outshines even the brightest globular in our Milky Way, Omega Centauri, and can be glimpsed even by better equipped amateurs under very favorable conditions, with telescopes starting at 10-inch aperture (see Leos Ondra's article in Sky & Telescope, November 1995, p. 68-69). The Hubble Space Telescope was used to investigate globular cluster G1 in mid-1994 (published April 1996). While the easiest, G1 is not the only M31 globular cluster which is in the reach of large amateur telescopes: Amateur Steve Gottlieb has observed 18 globular clusters of M31 with a 44cm telescope. With their 14-inch Newton and CB245 CCD camera, observers of the Ferguson Observatory near Kenwood, CA have photographed G1 and four fainter M31 globulars. Barmby et.al (2000) have found 435 globular cluster candidates in M31, and estimate the total number at 450 +/- 100.

The astrophotographer is even better off, as he can gather the fainter light of the fine detail in the spiral arms, as in our image: Amateurs can obtain most striking pictures even with inexpensive equipment, from wide-field exposures to detailed close-ups. Also in photography, better equipment pays off, as is demonstrated by our image, which was obtained by (and is courtesy of) Texas amateur Jason Ware, with a 6-inch refractor. More information on this image is available.

The brightest star cloud in the Andromeda galaxy M31 has been assigned an own NGC number: NGC 206, because William Herschel had taken it into his catalog as H V.36 on the grounds of his discovery observation of October 17, 1786. It is the bright star cloud at the upper left, just below a conspicuous dark nebula, in our photograph (very conspicuous in the larger photo).

Despite the large amount of knowledge we now have about the Andromeda Galaxy, its distance, though among the best known intergalactic distances, is not really well-known. While it is well established that M31 is about 15-16 times further away than the Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC), the absolute value of this measure is still uncertain, and in current sources, usually given between 2.4 and 2.9 million light-years - a consequence of the uncertainty in the LMC distance and thus the overall intergalactic distance scale. E.g., the semi-recent correction from data by ESA's astrometrical satellite Hipparcos has pushed this value up by more than 10 percent, from about 2.4-2.5 to the about 2.9 million light-years we use here.

Under "normal" viewing conditions, the apparent size of the visible Andromeda Galaxy is about 3 x 1 degrees (our acurate value, given above, is 178x63 arc minutes, while NED gives 190x60'). Careful estimates of its angular diameter, performed with 2-inch binoculars, by the French astronomer Robert Jonckhere in 1952-1953, revealed an extension of 5.2 times 1.1 degrees (reported by Mallas), corresponding to a disk diameter of over 250,000 light years at its distance of 2.9 million light years, so that this galaxy is more than double as large as our own Milky Way galaxy ! Its mass was estimated at 300 to 400 billion times that of the sun. Compared to the newer estimates for our Milky Way galaxy, this is considerably less than the mass of our galaxy, implying that the Milky Way may be much denser than M31. These results are confirmed by new estimates of the total halo masses, which turn out to be about 1.23 trillion solar masses for M31, compared to 1.9 trillion for the Milky Way (Evans and Wilkinson, 2000).

The Hubble Space Telescope has revealed that the Andromeda galaxy M31 has a double nucleus. This suggests that either it has actually two bright nuclei, probably because it has "eaten" a smaller galaxy which once intruded its core, or parts of its only one core are obscured by dark material, probably dust. In the first case, this second nucleus may be a remainder of a possibly violent dynamical encountering event in the earlier history of the Local Group. In the second case, the duplicity of Andromeda's nucleus would be an illusion causes by a dark dust cloud obstructing parts of a single nucleus in the center of M31.

Up to now, only one supernova has been recorded in the Andromeda galaxy, the Supernova 1885, also designated S Andromedae. This was the first supernova discovered beyond our Milky Way galaxy, on August 20, 1885, by Ernst Hartwig (1851-1923) at Dorpat Observatory in Estonia. It reached mag 6 between August 17 and 20, and it was independently found by several observers. However, only Hartwig realized its significance. It faded to mag 16 in February 1890.

Messier 32

Elliptical Galaxy M32 (NGC 221), type E2, in Andromeda

A Satellite of the Andromeda Galaxy, M31

Right Ascension 00 : 42.7 (h:m)

Declination +40 : 52 (deg:m)

Distance 2900 (kly)

Visual Brightness 8.1 (mag)

Apparent Dimension 8x6 (arc min)

Discovered 1749 by Guillaume-Joseph-Hyacinthe-Jean-Baptiste Le Gentil de la Galaziere (Le Gentil).

Messier 32 (M32, NGC 221) is the small yet bright companion of the Great Andromeda Galaxy, M31, and as such a member of the Local Group of galaxies. It can be easily found when observing the Andromeda Galaxy, as it is situated 22 arc minutes exactly south of M31's central region, overlaid over the outskirts of the spiral arms. It appears as a remarkably bright round patch, slightly elongated at position angle 150-330 deg, and is easily visible in small telescopes. Its ellipticity is about E2, i.e. the smaller diameter, or axis, or its elliptically shaped image, projected along our line of sight, is about a fraction of 0.2, or 20 percent, shorter than its larger axis.

M32 is an elliptical dwarf of only about 3 billion solar masses, and a linear diameter of some 8,000 light years, very small compared to its giant spiral-shaped neighbor. Nevertheless and surprising for such a small galaxy, its nucleus is of comparable properties as that of M31: About 100 million solar masses, 5000 suns per cubic parsecs, are in rapid motion around a central supermassive object. Because of this nucleus, M32 is sometimes classified as cE2 instead of simply E2, e.g. by NED.

Near the center of this galaxy, the sky would be dominated by this object, and full with the members of this galaxy, while at the edges, only one hemisphere would be filled with them, the other showing only few outlying stars and the intergalactic space. Toward M31, this galaxy would give a fascinating view in the night sky of a virtual astronomer in the outskirts of M32.

M32 appears to us superimposed over the spiral arms of greater M31. Therefore, it is of interest if it lies before or behind the great galaxy's disk. Spectroscopic investigations have not shown any absorption which would be expected if its light had passed the interstellar matter in M31's disk, which suggests that M32 is closer to us than that portion of M31.

The radial velocity of M32 has been measured at 203 km/s (R. Brent Tully) or 205 +/- 8 km/s (NED) in approach in the heliocentric system, i.e., toward our Solar System; corrected for galactic rotation, M32 is currently about at rest (RV=0) w.r.t. the Milky Way's Galactic Center. Compared to M31, it is approaching about 100 km/s slower, and considering its closer distance, it is apporaching M31 at this velocity in the radial component.

M32 and the other bright companion of M31, M110, are the closest bright elliptical galaxies to us, therefore also the among best investigated. They were both first resolved into stars by Walter Baade in 1944 with the 100-inch Hooker telescope on Mt. Wilson when he also resolved the nucleus of M31 (Baade 1944). Baade recognized that their stars were mostly old population II stars, and about as bright (and thus at roughly the same distance) as M31, thus confirming their proximity to the large spiral galaxy. There are remarkable differences between these dwarf galaxies: While M32 is a typical generic elliptical, compact and of high surface brightness, M110 is much more loose, of lower surface brightness, and exposes peculiar structures; now, M110 is often classified as a dwarf spheroidal galaxy instead of elliptical. Remarkably, M32 has no globular clusters (again, in difference to M110 which has 8).

M32, like typical elliptical galaxies, is mostly made up of old stars, of which only the lower-mass, intrinsically fainter ones have survived to now; as usual in such old populations (e.g., also in globular clusters), the more massive stars have presumably ended their active, nuclear-burning lives long ago - they are now white dwarfs or neutron stars. However, spectra and color of this galaxy (M32 has an overall spectral type of G3 and color index B-V = +0.75) indicate that its stars have chemical abundances different from those in old globulars which are poor in heavy elements. Instead, there seems to be a population of stars richer in heavy elements, which are apparently much younger, only 2 or 3 billion years old, mixed between the old stars as minor contamination.

Between the stars of M32, some planetary nebulae have been found, but no clouds of interstellar matter, neither gas clouds nor dust lanes nor neutral hydrogen, nor any open clusters. Apparently, M32 is no more able to form any new stars, but consists of old stars, mixed up with some of intermediate age. According to investigations of multicolor data, this stellar population is much more similar to that of much larger elliptical than that of typical dwarfs of its size, which are typically of dwarf spheroidal type.

Novae occur in M32 occasionally. One recent nova was discovered in M32 on August 31, 1998 within the Lick Observatory Supernova Search Program by a team of astronomers from the University of California at Berkeley headed by E. Halderson (1998). This nova occurred about 28.5 arc seconds west and 44.7" south of the galaxy's nucleus and reached mag 16.5. Supernovae have not yet been observed in this galaxy.

As its stellar population, size of nucleus, and compactness indicate, M32 looks more like a much larger elliptical galaxy. Therefore, it seems possible that M32 was once much larger, but lost its outer stars, and also all globular clusters it may have had, in one or more past close encounters with the Andromeda Galaxy M31. These stars and clusters were absorbed by, or integrated in, and are now part of the halo of M31. That M32 has recently undergone a closer encounter with its larger neighbor is suggested because it apparently caused and left disturbances in the big galaxy's spiral pattern.

M32 was the first elliptical galaxy ever discovered, by Le Gentil on October 29, 1749. Charles Messier remarked in his description that he had first seen this object in 1757 (his first record of an observation of one of "his" objects), cataloged it on August 3, 1764, and included M32, together with M110, in his drawing of Andromeda's "Great Nebula". Halton Arp has included it as No. 168 in his Catalogue of Peculiar Galaxies.

Messier 110

Elliptical Galaxy M110 (NGC 205), type E6p, in Andromeda

A Satellite of the Andromeda Galaxy, M31

Right Ascension 00 : 40.4 (h:m)

Declination +41 : 41 (deg:m)

Distance 2900 (kly)

Visual Brightness 8.5 (mag)

Apparent Dimension 17x10 (arc min)

Discovered by Charles Messier in 1773.

Messier 110 (M110, NGC 205) is the second brighter satellite galaxy of the Andromeda galaxy M31, together with M32, and thus a member of the Local Group.

Curiously, this galaxy was discovered by Charles Messier on August 10, 1773, as described in the Connaissance des Tems for 1801, and depicted on his fine drawing of the "Great Andromeda Nebula" and its companions published in 1807. However, Messier did never himself include this object in his catalog, due to unknown reasons, perhaps a certain sloppiness in recording. It was the last additional object, added finally by Kenneth Glyn Jones in 1966. Independent of Messier's discovery, Caroline Herschel independently discovered M110 on August 27, 1783, little more than 10 years after Messier, and William Herschel numbered it H V.18 when he cataloged it on October 5, 1784.

The small elliptical galaxy M110 is at about the same distance as the Andromeda galaxy M31, about 2.9 million light years, as confirmed by Walter Baade in 1944, when he resolved it into stars (Baade 1944). It is of Hubble type E5 or E6 and is designated "peculiar" because it shows some unusual dark structure (probably dust clouds). M110 is now often classified as a dwarf spheroidal galaxy, not a generic elliptical one (this would make it the first ever known dwarf spheroid, of course). However, as it is much brighter than typical dwarf spheroids, Sidney van dan Bergh has recently introduced the term "Spheroidal Galaxy" for this and similar galaxies, including Local Group members NGC 147 and NGC 185. M110's mass was estimated to be between 3.6 and 15 billion solar masses.

Apparently, despite its comparatively small size, this dwarf elliptical galaxy has also a remarkable system of 8 globular clusters in a halo around it. The brightest of them, G73, is of about 15th magnitude and thus within the reach of large amateur telescopes; Steve Gottlieb has observed it with a 44-cm telescope together with M31 globulars, and amateurs at the Ferguson Observatory near Kenwood, CA obtained a CCD image showing 7 of them with their 14-inch Newtonian and CB245 CCD camera (via the M31 GC images page).

m033_300mm-f056-400iso-60deg.jpg